How much music have you consumed in the last week? “That’s easy,” you say probably. After all, the music is quite well countable. You can either count the number of songs, OR – if you want to be even more precise – you can count the total seconds the music sounded. So what’s the loophole, here?

Well, the music at first glance really looks as countable as cheese, potatoes or crows on a telegraph pole. But that is true only as long as you count it for yourself solely. If the music is to be traded, suddenly all traditional metrics are of no use anymore. Not convinced? Well, then next time you go to music store, try to ask for 245 seconds of rock-n-roll and 720 seconds of classical music, please, packed separately, so it does not mingled. Do you get the point?

Measuring Medieval music

In fact, the sales units of music have changed significantly throughout history. In the oldest times, music could not be stored. There was no medium on which to record the music, so the music was only sold per unit of experience. In today’s notion, it would be a unit of measure like “one concert“. As with other medieval measures (such as thumb or elbow) there was no standardized form of that measure, and so the length (and intensity of the concert) depended largely directly on standard of the individual musicians.

The invention of a gramophone (and soundtrack recording) had brought a fundamental revolution in music units. Music suddenly stopped being sold in experience units (which will have its historical implications, but we will revisit it later), but the the music medium has become the unit of music. Firstly (gramophone) vinyls, then magnetic tapes and CD’s ultimately. Since most of us were born already into this set-up, we don’t find it strange. However, when you get a little historic zoom-out, you may realize that selling music by a “medium unit” is like selling sausages by area of the packaging or health by number of blood cans. On other words, it is not important how much benefit you buy in the package, literally, only the size of the package matters.

The invention of a gramophone (and soundtrack recording) had brought a fundamental revolution in music units. Music suddenly stopped being sold in experience units (which will have its historical implications, but we will revisit it later), but the the music medium has become the unit of music. Firstly (gramophone) vinyls, then magnetic tapes and CD’s ultimately. Since most of us were born already into this set-up, we don’t find it strange. However, when you get a little historic zoom-out, you may realize that selling music by a “medium unit” is like selling sausages by area of the packaging or health by number of blood cans. On other words, it is not important how much benefit you buy in the package, literally, only the size of the package matters.

Generation after generation, we had learned to live with this music measuring “defect” and kept on buying albums. There were only two units in the album metric system: 1 Album and 1 Single and it was set that the Album is bigger than Single in terms of songs or seconds. It is crucial to note (for out further discussion) one more important fact: According to the (back-then) contemporary music sales stats, the Albums to Singles ratio was 179: 1. Thus, the Single’s accounted for only about 0.5% of all the music sold.

The root cause is the Apple, not the Newton

However, as a unit of music, the Album actually only suited one player in the music market: the music studios that were recording the albums. If you happen to be one of elder, you will surely remember moment when you bought a cassette or CD and you liked very much 2, maybe 3 songs from the whole album. The rest of it was, um, sort of crap. This, of course, irritated people, and as the music industry (some what negligibly) allowed computer technology to use magnetic tapes and CD’s to record data, these media became the Trojan horse music business. Unlike the vinyls, CD’s could have been burned (and thus copied) already by the regular people, which in turn led to a significant increase in piracy and the emergence of a separate section of shabby market stalls. Moreover, compact discs (unlike tapes) did not damage the original when copying. However, the final blow for the album metric unit was yet to come.

The figurative last nail into Album’s coffin was an apple. In order to re-balance a reputation from the gravitational law (when fame was treacherously attributed entirely to Newton, and the apple got out of it with mere proverb “didn’t fall far from the tree.”) Taught by this crisis, this time the apple left nothing to chance and under its English pseudonym “Apple Inc.” brought the World the iTunes application. (which broke the album metric system for good). In Apple products, the music was suddenly available, God help us, by pieces. The world order has turned again from the head to its feet and you could buy (in the sense of the above analogy) sausages by pieces rather than by package loads.

The figurative last nail into Album’s coffin was an apple. In order to re-balance a reputation from the gravitational law (when fame was treacherously attributed entirely to Newton, and the apple got out of it with mere proverb “didn’t fall far from the tree.”) Taught by this crisis, this time the apple left nothing to chance and under its English pseudonym “Apple Inc.” brought the World the iTunes application. (which broke the album metric system for good). In Apple products, the music was suddenly available, God help us, by pieces. The world order has turned again from the head to its feet and you could buy (in the sense of the above analogy) sausages by pieces rather than by package loads.

Those less patient could say “and here we can call it off, right?” After all, the music can still be bought in pieces (songs) until today. In fact, another important step in measuring music has made more difficult to measure again. If the iTunes step was called “unpacking music to pieces,” there has been another “re-wrap” over the past decade. Don’t worry, I don’t mean any parental responsibilities associated with distinct, uh, smell. (Although bad languages say that this re-wrapping has led to many: How is it fairly called? Poops?)

Thanks to companies like Spotify, the music began to be sold as subscription. Suddenly the pieces were no longer important, you could literally tap the whole stream of music. This move greatly simplified the music business, while the unit price of the song being in cents, collecting (remotely) a few cents from you after each song played is as if the bus driver stopped every 100 meters of ride to collect from all passengers a small fee for next 100 meters to come. (If it still seems pretty doable to you, think aircraft in very same analogy).

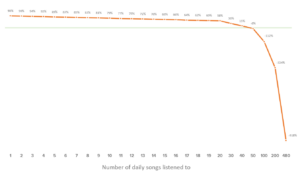

However, unlike a monthly transport ticket or fitness gym membership, Spotify subscription, even though linked to time interval (e.g. a month), does not assume that you will “run the service the whole month continuously” in this subscription. Thanks to great data from the book of A. McAffee and E. Brynjolfssona: “MACHINE, PLATFORM, CROWD“ , which depicts Spotify model in more detail, I can introduce you to Spotify’s gross margin (excl. overhead costs). For given number of songs listened to by the regular user, their margin looks something like this:

From numbers above it is clear that Spotify firmly hopes that you will not listen to more than 45 songs per day (or 1300 per month). So, something like an eat-all-you-can restaurant that also assumes you haven’t come to her (literally) eat yourself over to the other world. The catch is, of course, that not everyone pays for Spotify. According to avaliable public data some form of the payment provides every second Spotify’s customer. Thus, leaving advertising revenue aside (and making a somewhat strong assumption that a paying user has more or less similar consumption as free user), Spotify can be profitable if its average user consumes no more than 750 songs a month.

But let’s revert from Spotify business model, back to what the emergence of music streaming services meant for the music units. The advent of iTunes brought us the easiest way to measure music, but Spotify subscriptions have made the clear waters muddy again. On top of that, though advent of iTunes and music streaming services has been massive, they have failed to cover the entire music market. And thus we have been left with somewhat strange cocktail of parallel, different music units, making the total commercial music consumption measurement a mess again. From Jake Brown’s data, (and few other music blogs) it is clear, that companies in the industry managed to agree on linking the different music units. Thus finally, at the end of this historical excursion, we worked our way to music being measured in three main units:

1 500 SEA = 10 TEA = 1 ALBUM , where

SEA = any (even unfinished) streaming of exactly 1 song, TEA = purchase (or download) of 1 paid song and ALBUM = simply the album as we know them from past.

Therefore, let me conclude this blog with some practical stats (potentially interesting to you, if you happen to swim through music topics) that arise from the music measurements units. Consumption of music with the advent of its media, digital purchasing and streaming services has increased rapidly. That might sound like it is worth being a musician, because the demand for listening to music is still growing.

In reality, this is so because we can now afford a trick, that was nor possible in “one concert unit” times: We are able to listen to the artists even after their death. However, the more crucial information is that the total amount of money people put into music (relatively steeply) fall from generation to another. According to the SoundScanData 2016 2016 study, in year of 2016 people paid for the music equivalent of 561 million albums. In 2000 it was 785 million albums. Consequently, there are 29% fewer units of money in music sales industry, which ever increasing number of living artists must gradually more and more share with the passed away ones. So if you’re considering a second career in your life, the music will probably be a very muddy path.

Publikované dňa 9. 9. 2019.